A Brief History Of The Roman Empire, Part 4: Marius And Sulla

You probably know something about Ancient Rome. Julius Caesar used his army against the government to establish himself as dictator for life. He was then assassinated as a vain attempt at restoring the Republic. Before we talk about Caesar we need to discuss Gaius Marius. Despite the Gracchi being put to sleep, the number of soldiers who are eligible for service was shrinking at an alarming pace.

The Marian Reforms

Marius, a talented commander who came from humble origins and married into the Julii patrician family. Marius distinguished himself in various campaigns in North Africa alongside a gifted young lieutenant of his named Cornelius Sulla. However, his lasting impact on Roman military would be in 104 BC when the Cimbri and Teutones, Germanic tribes, defeated several Roman legions, and threatened Italy.

Marius was given the task of rebuilding the fallen legions from scratch. To do this, he eliminated all property requirements for enlistment. Rome had begun to recruit from the landless poor in dire emergencies, but Marius made it standard policy — military service would no longer be a civic sacrifice but a career. The state would pay professional soldiers for their service, which would last decades. They were then allowed to settle on conquered lands after they had finished.

Bust of Marius. By © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 4.0

By all accounts, Marius’s armies were better trained, better disciplined and better organized than any of their predecessors — but they created a fundamentally different political dynamic. In the past, soldiers were part-time stakeholders in the Republic. They served to defend their homes and interests. Now, soldiers were fighting for their commanders — because it was their commanders who made sure that they were paid, their commanders that led them to victory and booty, their commanders that made sure they were settled on good farmland when their decades in the legions were up.

The new Roman legions created economic opportunities for Rome’s underclass, but their men were loyal to the people who paid them — which, in effect, was not the Roman state.

It was for this reason that Emperor Septimius Severus, hundreds of years later, would recommend his sons to “enrich the soldiers and scorn all other men.”

Marius, his darling nephew, would be elected consul five more times between 104-100 BC and would continue to hold Rome’s highest office until his death during his last term. His former lieutenant Sulla would be antagonized repeatedly.

Marius and Sulla

King Mithridates VI, Pontus invaded Roman territory in modern-day Turkey in 88 BC. An army was then raised to respond. Sulla was at the time a sitting consul and was given command of the army. He was sent to defend Roman territories and retaliate against invaders.

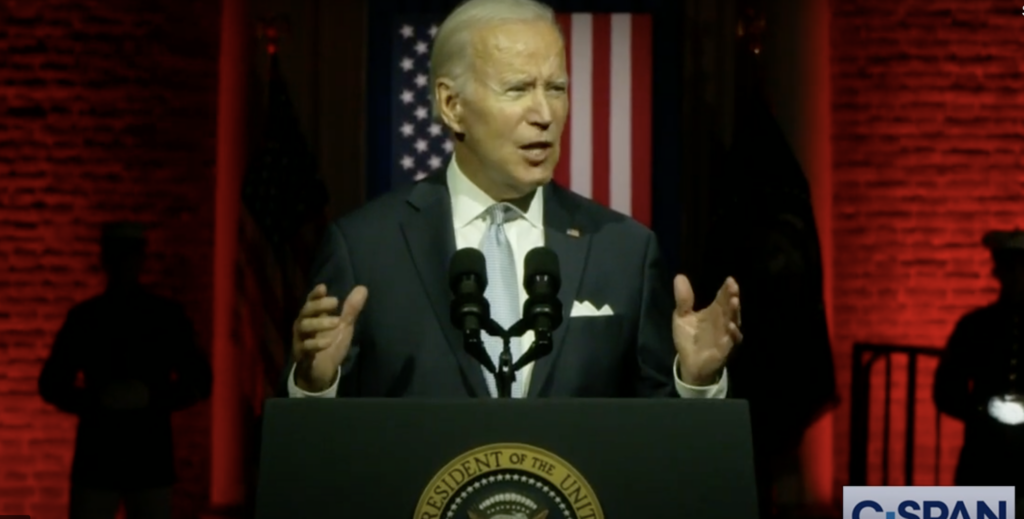

Getty Images.

Commanding such an operation was a high-profile task and offered great prestige. So Marius and his Senate allies worked together to remove Sulla from his command and to give it to Marius, while Sulla and his army marched out. Marius won and his men captured Sulla’s forces. They informed Sulla that Marius was now in command, and that he had to step down.

Sulla quickly killed Marius’s messengers and turned his army around. He put Anatolia in a stand and focused his attention on driving Marius, his comrades, out of Rome. It was the first time a Roman army would march on their own capital — although it would not be the last.

Cornelius Sulla’s Entry into Rome. Getty Images

While this was taking place, Mithridates kept busy Massacring tens to thousands of Roman civilians Sulla’s army advanced into territory to defend it, but political quarrels won out.

Marius was forced out of the city to escape for his safety while his closest friends were killed. Sulla was satisfied Marius had been left to pasture, and his closest supporters were secure. He then fled the city to confront the foreign invasion that started this mess.

Roman Republic in the First Mithridatic War 85 B.C.

Marius, on the other hand, was back in North Africa licking his wounds as he consolidated support. Marius was absent while Sulla was away. In 87 BC, Marius led an army of his own to Rome and expelled approximately 100 of Sulla’s political allies. He then seized control over the government. Marius was elected to the consulship for a record 7th time. He died two weeks later, leaving behind his many allies.

At this point, the Mithridatic invasion was pushing all the way to Greece. Sulla’s forces were heavily engaged and he couldn’t leave. However, once the invading army was defeated and peace terms had been reached in 85 BC, Civil War resumed.

Gnaeus Pompius and Marcus Licinius Crassus were two big names who made a name of themselves in this period. They would be later remembered as history’s greatest personalities. “Pompey the Great” But at that point, it was simply known as “the adolescent butcher” — Pompey began serving under Sulla at the tender age of 19 and his ruthlessness during the war was infamous.

By 82 BC, Sulla had re-established control of the city and declared himself dictator for life — he also ordered hundreds of prominent Romans put to death and put many more on a “proscription list.”

Public Domain. By Silvestre David Miys Wiki Commons.

The proscription was a Sullan innovation where a citizen was declared an enemy of the state and marked for death — the catch was that the property of the proscripted was nationalized and anyone who killed them was entitled to a share of it as a bounty. This replenished the public coffers that had been completely exhausted during the Civil War. They also created a reign of terror when hundreds of prominent Romans were brutally killed in the streets. Their heirs were left destitute and disinherited, and their murders were rewarded with small fortunes.

Crassus, whose wealth was taken by the Marians during the war, gave birth to a Massive Fortune on the proscription Stolen property can be bought He bought a fraction of the investment and continued to grow it through other dubious firesales until becoming the richest man in Rome.

Crassus was not liked by anyone.

Hundreds of Romans died during the Proscriptions. Some were simply for being related to the wrong people. But one person was able to escape by the skin his teeth. Marius’s young nephew, Julius Caesar.

Gaius Julius Caesar

Caesar was only a teenager when Sulla had his name added to the list of the damned — but he had already been married off to Cornelia, the daughter of Cinna, one of Marius’s top lieutenants. Sulla ordered the boy to divorce her — marriages often signified political alliances and this particular union was unacceptable.

Caesar Refused. He was added to the list.

The Julii were one the most distinguished patrician families in Rome, dating back to the foundation of the city. They are believed to be the direct descendants from Venus. Although the Caesares family might have supported the wrong horse during the civil war, it was still a crime to aid or comfort the condemned. Caesar’s friends in rural areas provided shelter for Caesar while his powerful friends at Sulla’s Court pleaded for the boy’s life.

Sulla eventually gave in to his feelings, though it was very reluctant. Although Sulla wouldn’t live to see the boy grow up, he did have a glimpse of his future. Sulla would mention that he made the decision to save the young man in his memoirs as one of his greatest regrets. “many a Marius” in Caesar.

Caesar, recognizing Sulla’s second thoughts about saving his life, quickly left the stage to pursue a military career in one of the provinces. This was before Rome’s first dictator-forlife changed his mind. Sulla meanwhile, ruled for three years, from 82 BC — 79 BC, before stepping down as dictator-for-life, one year prematurely.

Bust of Sulla. Public Domain. Wiki Commons.

Sulla used all of his power to Reform the state — introducing new requirements and restrictions for holding office and passing various constitutional reforms that in his view eliminated roots of corruption — including the diminishment of the office of Tribune of the Plebs, that constant source of rabble-rousers. Sulla at least cast Heself as a restorer of the Senate and republican virtue, in contrast to the depraved Marians, and spent his year of retirement hoping that his achievements would protect future generations of Romans from … men exactly like him.

Nevertheless, Sulla’s ‘do as I say, not as I do’ style of statesmanship proved unpersuasive.

RELATED: A Short History Of The Roman Empire Part 1: The Founding Of Rome

RELATED: A Brief History Of The Roman Empire, Part 2: The Public Thing

RELATED: A Brief History Of The Roman Empire, Part 3: Land Reform And The Era Of Gracchi

CLICK HERE TO GET THE DAILYWIRE+ APP

“From A Short History of the Roman Empire, Part 4 – Marius and Sulla“

“The views and opinions expressed here are solely those of the author of the article and not necessarily shared or endorsed by Conservative News Daily”

" Conservative News Daily does not always share or support the views and opinions expressed here; they are just those of the writer."

Now loading...