A history of Hollywood’s greatest failures – Washington Examiner

The article discusses Tim Robey’s book, ”Box-Office Poison: hollywood’s Story in a Century of Flops,” which explores the phenomenon of major film flops from 1916 to 2019. It addresses why audiences often take pleasure in Hollywood’s failures, emphasizing that these failures allow the public to exert their influence over the industry by refusing to support unappealing projects. The piece highlights notable flops, including instances from the past year, like francis Ford Coppola’s “Megalopolis” and sequels that did poorly. Robey argues that the existence of cinematic failures reveals that financial backing and star power do not guarantee success in film. He reflects on the peculiar charm of flops, suggesting that many ultimately gain a cult status or recognition for their artistry over time, despite initial failures. The book discusses several historic flops alongside modern ones,illustrating how the landscape of filmmaking has changed,especially highlighting the era of streaming services which has altered how flops are treated.

A history of Hollywood’s greatest failures

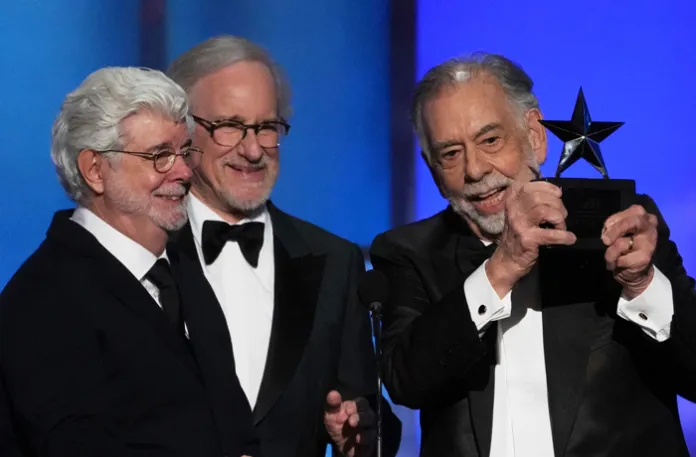

When a novel misses the mark, an opera sinks like a stone, or a Broadway show closes up shop, few care beyond the niche contingent conversant in the inside baseball of the respective art form. By contrast, when large-scale, grandly budgeted movies prove ruinously unprofitable at the box office, even amateur cinephiles find themselves doubled over with glee. Why do we derive such pleasure from the fiascos that emanate from Hollywood? The last year in flops was particularly fertile: Francis Ford Coppola self-financed the disastrous Megalopolis, the Joker sequel came a cropper, and even the Mad Max spinoff spun to nowhere worth going.

Part of the pleasure we take in flops is that we, the condescended-to public, get a say in the matter: We are free to participate in cinematic democracy by declining to buy a ticket. And if enough of us do so, Hollywood has another Gigli on its hands. The very existence of film flops provides reassurance that access to vast sums of money and pools of “talent” is no guarantee of wisdom, taste, or predictive powers. Whichever brilliant studio greenlit Madame Web, The Flash, or Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny presumably felt certain that they had their finger on the pulse of the public. But, in the fullness of time, they were proven wrong.

In an agreeably nasty new book, Telegraph arts writer Tim Robey attends to Gigli and 25 other notorious flops that, spanning 1916 through 2019, encompass virtually the entire history of the motion picture medium as it existed prior to COVID-19. That is a crucial distinction since, as Robey notes, the pandemic wrought such havoc on movie theater attendance that a flop was no longer a unique or even particularly interesting occurrence. “Studios now have a convenient burial plot for their most embarrassing product, which can be swiftly sold off to streaming services and thereby submerged with minimal public exposure,” writes Robey, who longs for the days when flops were big, bold, and wide out in the open.

“They’re the medium’s weirdos, outcasts, misfits, freaks,” he writes. “They can be reappropriated after the event as camp treats; they can linger, Ozymandiaslike, as monuments to studio hubris, hobbled and crumbling; or they can electrify decades later for reasons of genuine artistry, as misunderstood, radical, ahead of their time.”

The last category is not to be overlooked since, notwithstanding their initial rejection, several of the films discussed here are acknowledged as major achievements. For example, Robey opens the book with D.W. Griffith’s 1916 masterpiece Intolerance, a film that offers a kind of digest of world history, from Babylon to America in the early 20th century. “Intolerance wound up being four films in one, set across four historical time frames spanning 2,500 years of human civilization, which were daringly crosscut to illustrate [Griffith’s] overarching theme,” he writes. That the film cost millions (estimates range from $1.9 million to the implausibly high $8.4 million), and that Griffith fecklessly underwrote its overruns, does not diminish its compelling sweep. “With his fulminating, self-involved pleas for harmony, and all the historical hopscotching, Griffith was guilty of badly misjudging the public mood,” Robey writes, but happily, public moods change, and the epic remains available for rediscovery.

A number of Golden Age-era flops are treated with comparable kindliness, including Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Howard Hawks’s Land of the Pharaohs (1955). These productions may have been ill-timed or compromised in their making, but they remain honorable despite moviegoers’ disinterest. As the decades roll by, however, flops become increasingly indefensible, and the book becomes ever more amusing. By the time Robey turns to the 1990s, we start to encounter flops in their recognizable modern iteration: projects that were not defeated by an excess of artistic ambition, or ignored because of bad timing, but were undertaken thoughtlessly and greedily.

For example, director-star Dan Aykroyd’s repellently unfunny 1991 horror-comedy Nothing But Trouble, starring Chevy Chase as a financial adviser who, having made a wrong turn into the sticks, falls into the clutches of a delirious senile judge, traces its origins to a movie night attended by Aykroyd, his brother Peter, and producer Robert K. Weiss. “They opted for Clive Barker’s Hellraiser, a chiller so outlandish it had half the audience in hysterics,” Robey writes. “The idea of a gross-out horror romp, getting crowds to laugh and scream simultaneously, was hatched on the way out.” Not exactly a eureka moment, but Warner Bros., emboldened by the success of outré titles such as Beetlejuice and distracted by The Bonfire of the Vanities, ponied up the money. John Candy and Demi Moore co-starred. “They had huge comedy stars handling a comedy — what could go wrong?” Robey writes. Indeed.

Then there is the Coen brothers’ preposterously overdesigned and overbudgeted ($25 million) The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), which was backed by Warner Bros. on the goofy idea that what the sibling auteurs needed to break through to the masses was a big-shot producer (Joel Silver) and a few high-end stars (Paul Newman). “The fact that it was a Coen film with a Silver-boosted budget and name stars might have struck Warner Bros. initially as a bumper scenario,” Robey writes, “but the vexing result was how the elements actually subtracted from one another.” The U.S. gross: $2.8 million.

Meanwhile, the 1995 pirate saga Cutthroat Island, starring Geena Davis and, after actual movie stars abstained, Matthew Modine, was bankrolled by Carolco in full awareness of its imminent demise. “We knew from that point that if we lost Cutthroat Island as well, bankruptcy would be inevitable,” a studio executive said. “If we made the film, there was at least some chance we could survive.” It’s hard to imagine a flimsier pretext to plow through $98 million to $115 million (the estimated budget for the film). Then there is Speed 2: Cruise Control (1997), which was embarked upon, seemingly, because director Jan de Bont’s contract for the original, good Speed required his involvement in whatever sequel was whipped together. Happily for him, distressingly for us, Keanu Reeves was free to bow out. Sandra Bullock took the money and swam.

The turn of the millennium is heralded by the likes of the sci-fi flick Supernova (2000), the remake of Rollerball (2002) that presented Chris Klein as an acceptable substitute for James Caan, and the Eddie Murphy vehicle The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002). This was an era, Robey notes, “when flops really did flop hard, spending ludicrous sums to repair unfixable problems.” This is also the section that may induce embarrassment in readers in their 30s or 40s. How many of us naively bought tickets for the likes of the Halle Berry version of Catwoman (2004) or the Ray Bradbury adaptation A Sound of Thunder (2005)? Well, not too many, though I plead guilty to seeing the latter, which featured special effects so bad that they resembled, as Robey puts it, those on a CD-ROM from 1993. The problem here was not too much money thrown at a spiraling production but far from enough: “Midway through production, one of the film’s cofounding entities, the snappily named German company QiX Quality International Effects GmbH & Co. KG Jan Fantl Filmproduktion, financially collapsed.” Oh, that explains it. Robey grades it an “F (or Z) for execution” but good-naturedly awards a “C+ for pluck and ambition.”

Fittingly, the book ends with a discussion of the 2019 film version of the musical Cats, starring, among others, a very pre-Eras Tour Taylor Swift. Robey sounds a melancholy note. “They already don’t make ’em like Cats anymore.”

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.

" Conservative News Daily does not always share or support the views and opinions expressed here; they are just those of the writer."