The Derek Chauvin Trial – Coverage to Ninth Day

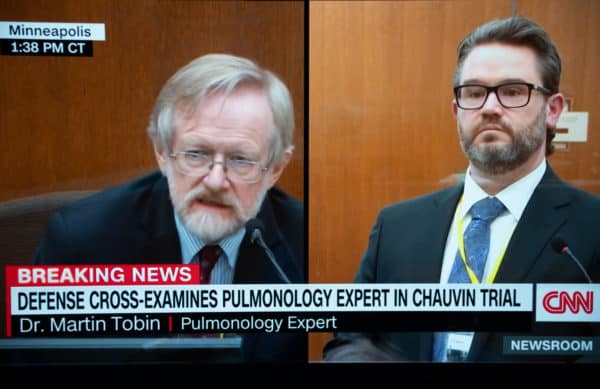

Day nine was all about how George Floyd died — the most important question in this case. The prosecution called Dr. Martin Tobin, a pulmonologist with impressive credentials. Prosecution lawyer Jerry Blackwell noted that the medical journal The Lancet calls Dr. Tobin’s book on mechanical ventilation (breathing) “the Bible.”

Dr. Tobin has been a paid expert witness in medical malpractice cases. When the prosecution contacted him about this trial, Dr. Tobin offered to waive his usual $500 an hour fee, because he has not done a criminal case before.

Mr. Blackwell asked Dr. Tobin what he thought George Floyd’s cause of death was. The doctor answered, “Mr. Floyd died from a low level of oxygen, this caused damage to his brain, and it also caused a PEA [pulseless electrical activity] arrhythmia, and that caused his heart to stop.” The doctor explained that other terms, such as asphyxia and hypoxia, all mean a low level of oxygen. He said the low level was the result of “shallow breathing . . . small breaths that weren’t able to carry the air through his lungs down to the essential area of the lungs that gets oxygen into the lungs and gets rid of the carbon dioxide.”

The doctor said several things led to Floyd’s shallow breathing: prone position, handcuffs, knee on neck, knee on back, knee on side. All this would lead to shallow breaths. He also said many times that pressure from lying on pavement, instead of something soft, like a mattress, also made it hard for Floyd to expand his lungs.

The jury got a lesson in lung anatomy. “Dead space” is the part of the lung air travels through before reaching the alveoli, the tiny air sacs where oxygen enters the blood. Incidentally, in severe cases of Covid-19 — and Floyd was positive — the alveoli don’t work properly.

Although both the police officers’ positions and George Floyd’s position changed, Dr. Tobin said that Mr. Chauvin’s left knee was on Floyd’s neck for more than 90 percent of the nine minutes and 29 seconds Mr. Chauvin had a knee on him. Mr. Chauvin’s right knee was on Floyd’s back for 57 percent of time, and at other times it was on Floyd’s arm or “rammed in against” the left side of Floyd’s chest. The doctor said this would all have similar effects on Floyd’s breathing.

Dr. Tobin explained that when a person breathes, the chest expands both front-to-back and side-to-side. A photo shows Mr. Chauvin’s hand pushing down on Floyd’s wrist, while it was handcuffed behind his back. Dr. Tobin said the pressure against Floyd’s back prevented the front-to-back movement that Floyd needed to breathe. Dr. Tobin said that in the case of Floyd’s left side, it was “as though a surgeon had gone in and removed the lung,” so he was totally dependent on his right lung.

Dr. Tobin used photos from the scene to argue that Floyd was using his fingers and knuckles to push up against the street and the squad car’s tire to try to open his chest. He said Floyd was lifting his shoulder to try to get more breathing room.

Dr. Tobin said that the knee on Floyd’s neck was extremely important because it kept air from getting through to the lungs. The hypopharynx is a very narrow part of the throat that has no cartilage to protect it from compression. The doctor said that at different times in the video, he could see Mr. Chauvin putting pressure on Floyd’s hypopharynx. If the hypopharynx is completely blocked, oxygen deprivation will cause a seizure or a heart attack within seconds.

When Floyd rolled his head face down against the street, the doctor thought he was trying to get leverage to expand his chest. This released some of the pressure on the hypopharynx. When Floyd’s head was to the side, there was greater pressure on the hypopharynx. Once the airway is 85 percent blocked, it takes much more effort to breathe, and at some point, a person can’t breathe anymore.

Dr. Tobin pointed to a moment when Mr. Chauvin’s toe does not touch the ground, suggesting that much of his weight was on Floyd’s neck area. The doctor calculated the weight on Floyd’s neck at that moment as 86.9 pounds. The sides of the neck expand as a person inhales, but the doctor said it doesn’t really matter whether Mr. Chauvin’s knee was on Floyd’s back, neck, or side. Any position, in combination with the pavement, could lead to shallow breathing.

The doctor explained that when we exhale, we do not exhale all of the oxygen from our lungs; we have a reserve. He used an illustration to show what are called the End-Expiratory Lung Volume (EELV) and the Residual Volume (RV). “The EELV is now really squashed down by the combinations of turning him prone and also having the knee on the back,” Dr. Tobin explained. “You’re seeing a 43 percent reduction in the EELV, which means, there is also a 43 percent reduction in his oxygen reserves, which means there is also a huge reduction in the size of the hypopharynx, because this is directly linked to the hypopharynx.”

The doctor talked about how hard Floyd’s body was working to keep breathing. “When you’re turned prone and with the knee on the back, now the work that Mr. Floyd has to perform becomes huge . . .with each breath, he has to fight against the street; he has to try to fight with the small volumes that he has; then he has to try to lift up the officer’s knee.” Dr. Tobin said that the other officer pushing down against Floyd’s handcuffed hands also pushed Floyd’s chest against the ground. “There is a huge increase in the work that Mr. Floyd was performing just to cope with what was happening below the neck, let alone what is happening above the neck.”

Dr. Tobin said that when the level of oxygen reaches 36, a person loses consciousness. George Floyd, a 46-year-old man, had a normal level of 89. Floyd lost consciousness at about 8:25pm. Dr. Tobin, who works in an intensive care unit, said he can tell by looking at a patient’s face whether the patient has lost consciousness. After Floyd blacked out, the amount of oxygen in his body went to zero in less than a minute. Mr. Chauvin lifted his knee off Floyd three minutes and two seconds after Floyd’s air supply was completely gone.

The doctor was aware of Floyd’s pre-existing medical conditions from the autopsy report, but said they made no difference. Nor did it make any difference that Floyd had been fighting police officers for 10 minutes. “A healthy person subjected to what Mr. Floyd was subjected to would have died.”

Dr. Tobin said Floyd’s paraganglioma tumor was not impotent because “one of the key things about a paraganglioma is that it’s called the ’10 percent tumor.’ This means 10 percent of the people with paraganglioma secrete extra adrenalin (which would have made Floyd’s condition worse). Well, that could be important, but 90 percent of them don’t secrete adrenalin.” The doctor added that when someone dies from a paraganglioma, it’s a sudden death. There are six reported cases of people with paraganglioma who died suddenly, but those people complained of headaches, and Floyd did not. Dr. Tobin said Floyd’s death was not sudden.

The doctor said it was important to note when Floyd was able to speak. He said that while Floyd was speaking, there was enough oxygen to keep his brain alive. However, he said that “if you can speak, you can breathe” is “a very dangerous mantra.”

Pulmonology Expert, Dr. Martin Tobin, is questioned by prosecuting attorney, Jerry Blackwell, during the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: © Pool Video Via Court Tv via ZUMA Wire)

“It’s a true statement, but it gives you an enormous false sense of security. At the moment that you are speaking, you are breathing, but it doesn’t tell you that you are going to be breathing five seconds later.” The doctor elaborated, saying that people speak only when they are exhaling. There must be inhalation before you speak. Floyd was talking for 4 minutes and 51 seconds, so his airway was not fully blocked for that period of time.

There is a moment in the video that shows Floyd’s leg kicking up backwards. The doctor said this is an involuntary reaction that indicates a fatally low level of oxygen going to the brain. “The brain is only 2 percent of our body weight but it takes 20 percent of our oxygen supply. . . . If you stop the flow of oxygen to the brain, you lose consciousness in eight seconds.”

On cross-examination, defense lawyer Eric Nelson said, “MPD officers have nowhere near your level of expertise . . . they are not even EMTs.” He said that while the doctor had the luxury of slowing down and repeatedly looking at the video — “literally hundreds of times” — the police were making decisions in real-time, based on far less medical knowledge.

Mr. Nelson said that the physics were constantly changing and could be different at each moment. Of the mathematical calculations the doctor made, Mr. Nelson said, “You’ve taken this case, and you literally boiled it down to a nanosecond.” Dr. Tobin disagreed, saying that he had given a chronology.

Mr. Nelson pointed out that Dr. Tobin is not a pathologist and doesn’t look at everything the way a pathologist would, but the doctor disagreed. “A pathologist is looking at the nanosecond of death.”

Doctor Tobin had mentioned that the back of the neck is very hard and can withstand pressure. Mr. Nelson asked the doctor if Mr. Chauvin’s knee had been on that spot, and the doctor conceded that “at times” it was.

Pulmonology Expert, Dr. Martin Tobin, is cross examined by defense attorney, Eric Nelson, during the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: © Pool Video Via Court Tv via ZUMA Wire)

The defense tried to turn the doctor’s negative view on If you can speak; you can breathe to his advantage, by pointing out that even doctors keep that expression in mind as they work. Doctor Tobin insisted that it’s a bad concept to teach police officers. Mr. Nelson also prompted Dr. Tobin to admit that the calculations he presented in court assumed an equal weight distribution on Mr. Chauvin’s right and left leg.

Mr. Nelson asked Dr. Tobin if Fentanyl can cause death from low oxygen. The doctor said it can, but that it puts patients into a coma. Doctor Tobin calculated Floyd’s breaths per minute from the part of the video in which Floyd was still breathing. He said Floyd’s breaths were too frequent to suggest that Fentanyl was causing respiratory failure. Mr. Nelson brought up the pill fragments that had been found in the back seat of the squad car in which Floyd had spent some time. If Floyd had swallowed Fentanyl-and-methamphetamine pills before getting onto the pavement, wouldn’t they reach peak effect in about five minutes? Dr. Tobin had to agree that they would.

The next witness for the prosecution was Daniel Isenschmid, a forensic toxicologist, who tested Floyd’s blood and urine. He compared their chemical contents to those of thousands of other patients, both living and dead. He said the concentration of drugs in blood may appear higher if the blood is taken after the patient dies.

Forensic Toxicologist, Dr. Daniel Isenschmid, testifies during the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: © Pool Video Via Court Tv via ZUMA Wire)

He had lots of charts showing that George Floyd’s Fentanyl levels were low compared to other samples in his database, but on cross-examination, Mr. Nelson pointed out that the findings presented for deaths with Fentanyl included patients who had died of other causes and the data were not limited to people who had died of recreational Fentanyl overdose. For all anyone knew, they could all have been shot dead or died in car crashes and were then found to have Fentanyl in their systems.

Dr. Isenschmid also compared Floyd’s Fentanyl levels to living people who were in DUI cases. Some were driving with higher levels of Fentanyl than were found in Floyd’s blood. Dr. Isenschimd called that “pretty amazing,” suggesting that Floyd’s Fentanyl level need therefore not be fatal. The doctor said the amount of methamphetamine in Floyd’s blood was about what someone with a prescription for the drug would take. There was morphine in Floyd’s urine, but he said it can stay in urine for a few days after someone takes morphine. He also found that Floyd smoked tobacco and marijuana and drank coffee.

Dr. Bill Smock, an emergency medical doctor with a specialty in forensic pathology, was hired by the state to testify for $300 an hour. He is a police surgeon, who accompanies SWAT teams in case someone gets hurt. He mostly just agreed with Dr. Tobin: “Floyd died of positional asphyxia. He died because he had no oxygen in his body.”

Dr. Smock said he ruled out other causes of death, including excited delirium, a controversial diagnosis not recognized by the American Medical Association or the American Psychiatric Association. He showed a chart of symptoms of excited delirium and said that Floyd did not have any of them.

He did not think Floyd died of an overdose because he didn’t think Floyd looked sleepy or lost awareness of where he was or what was happening. The doctor also did not see other signs of Fentanyl overdose, such as constricted pupils.

Dr. Smock talked about “air hunger,” which means being desperate to breathe. He told the court that saying “I can’t breathe,” is a sign of air hunger. In an opioid overdose, there is no air hunger because the patient falls asleep and then goes into a coma. The doctor said he never saw an opioid overdose in which someone had air hunger and cried out in pain.

On cross-examination, Dr. Smock conceded that methamphetamine — which Floyd had in his system — when combined with an opioid such as Fentanyl would produce a different kind of death from one caused exclusively by Fentanyl.

This was a good day for the prosecution. Its witnesses said what they were supposed to say and stuck to their guns. However, cross-examination was limited to subjects that came up on direct examination, so Mr. Nelson could not introduce new facts that were useful for the defense. The real test will come when the defense puts on its own experts, who will make a different case for how Floyd died. The trial continues on Friday.

Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin’s murder trial began yesterday, accompanied by all the expected theatrics.

Reverend Al Sharpton has held several press conferences recently, accompanied by members of George Floyd’s family and their attorney Ben Crump, who represented them in the civil suit against the city of Minneapolis, which resulted in a $27 million settlement. On Sunday, Rev. Sharpton spoke at a Baptist Church in Minneapolis, saying “Chauvin is in the courtroom, but America is on trial.”

On Monday morning, Rev. Sharpton again stood before the press and called George Floyd’s death a “lynching by knee.” He led those assembled as they took a knee for eight minutes and 46 seconds — the time that former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin restrained Floyd. Some of those surrounding Mr. Sharpton were wearing facemasks with “8:46” and a flatlined heartbeat printed on them. The group then chanted, “No justice! No peace!”

March 29, 2021, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Surrounded by family, Ben Crump and Al Sharpton took a knee for 8 minutes and 46 seconds after a press conference on the grounds of the Hennepin County Government Center. (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

Mr. Crump said this would be “a referendum on how far America has come in its quest for equality and justice for all,” and would determine “if we live up to the belief that all men are created equal.” One of George Floyd’s brothers told the press, “If we can’t get justice for a black man here in America, we will get justice everywhere else in America. This is a starting point.”

Inside the courtroom, the trial started with the prosecution’s motion to prohibit the defense from suggesting that George Floyd had been “malingering” which is “the act of intentionally feigning or exaggerating physical or psychological symptoms for personal gain.” Judge Peter Cahill informed both teams that it would be okay to say that George Floyd “appeared to be resisting,” but not that he “was resisting.”

The trial is being televised, but the jurors aren’t. During the selection, only jurors’ voices were broadcast, and they were assigned numbers to protect their identities. According to Court TV, the 12 jurors and two alternates are six men and nine women; ten under 50 and five over 50; eight whites, four blacks, and two who identify as multiracial.

The prosecution’s opening remarks were made by black lawyer Jerry Blackwell. He showed the jury the Minneapolis Police Department’s motto: “To protect with courage, to serve with compassion.” He told them that MPD officers take an oath that says they will never employ unnecessary force. Mr. Blackwell told the jurors, “You will learn what happened in that nine minutes and 29 seconds, the most important numbers you will hear in this trial are 9:29, what happened in those nine minutes and 29 seconds when Mr. Derek Chauvin was applying this excessive force to the body of Mr. George Floyd” — a number that did not match the “8:46” touted by Rev. Sharpton and the Floyd family earlier.

Mr. Blackwell then quoted what Floyd said as he lay on the ground in handcuffs, and said of Mr. Chauvin’s actions: “He doesn’t let up and he doesn’t get up.” He said that Derek Chauvin maintained his position with his knee on Floyd’s neck, even as he was told that Floyd did not have a pulse, and that Mr. Chauvin did not get up when a paramedic examined Floyd.

Mr. Blackwell said that “in your custody” is equivalent to “in your care,” and went through a list of witnesses he plans to call to demonstrate that Mr. Chauvin “did not administer care.” These witnesses will include:

- A use-of-force expert from Los Angeles.

- A police officer who was present at the scene and felt Mr. Chauvin used excessive force.

- Minneapolis Police Commander Katie Blackwell (no relation to Jerry Blackwell), who will testify about Mr. Chauvin’s training.

- A firefighter who wanted to take Floyd’s pulse and care for him.

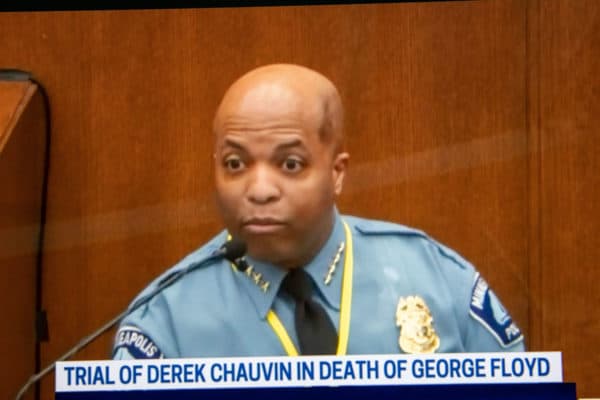

- Minneapolis Chief of Police Medaria Arradondo, who will say that Mr. Chauvin’s actions were excessive force.

- Bystanders who saw Floyd’s arrest.

- Several experts, such as doctors, toxicologists, and a medical examiner.

Mr. Blackwell expressed sympathy for police officers in general, saying that they have difficult jobs and need to make split-second decisions, but that “9:29” was not a split second decision. He then gave a “trigger warning” before playing the video of Floyd’s arrest, explaining that people in the video would be called as witnesses. Derek Chauvin seemed calm as the video played, alternating between watching the screen and writing on his notepad. When the video ended, Mr. Blackwell told the jury that bystanders were calling the police on the police. He told them about another witness who would be called, a 911 dispatcher who also “called the police on the police.”

Regarding the cause of Floyd’s death, Mr. Blackwell told the jury, “You can believe your eyes.” He added that experts will explain that “compression for 9:29 is enough to take a life.” and that further video evidence will show that Floyd died of oxygen deficiency, not a heart attack. Drawing attention to the autopsy report that described cardiopulmonary arrest as the cause of death, Mr. Blackwell said, “All that means is the heart stops . . . [it’s] another way to say death. Cause of death is death.”

Mr. Blackwell denied that Floyd died from an opioid overdose. Acknowledging that Floyd had heart disease, Mr. Blackwell said Floyd lived for years with the condition — until “9:29.” He concluded his opening statement by describing George Floyd as a “Covid survivor” whose life meant something to other people.

Derek Chauvin’s lawyer is Eric Nelson, who is contracted to defend police officers in Minneapolis. He began his opening statement outlining the concept of “reasonable doubt” and stated, “There is no political or social cause in this courtroom.” He also told the jury, “This case is about more than nine minutes and 29 seconds.” There had been an extensive FBI investigation, search warrants, and interviews with first responders and nearly 400 witnesses.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson and defendant Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: © Star Tribune / TNS via ZUMA Wire)

Mr. Nelson outlined what happened to bring Floyd to the attention of the police in the first place. A cashier at Cup Foods noticed that Floyd was using a fake $20 bill to pay for cigarettes. He asked Floyd twice to either pay for his cigarettes with real money or give the cigarettes back. Floyd refused, so the cashier called the police. The employee noticed a problem with Floyd’s behavior, and reported that he thought Floyd was under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Mr. Nelson told the jury they would hear about what happened in Floyd’s Mercedes Benz before the police arrived: Floyd took two pills and passed out. Two of his friends were in the car with him, and they panicked when they couldn’t wake him up. One called her daughter and asked her to come pick them up. The police arrived first, and Mr. Nelson claimed that bodycam footage will show that the officer who first drew a weapon on Floyd did so after Floyd refused to show his hands. When confronted by police, Floyd put drugs in his mouth to conceal them.

“When an officer responds to what is sometimes a routine and minimal event,” Mr. Nelson said, “It often evolves into a greater and more serious event.” Two search warrants were executed on Floyd’s car, revealing pills known as “speedballs,” which are manufactured to have the appearance of Percocet, but are a mixture of uppers and downers. Partially dissolved pills — found in the squad car that Floyd refused to sit in — contain Floyd’s DNA.

Mr. Nelson contrasted Mr. Chauvin’s build (5’9” and 140 pounds) with George Floyd’s (6’3” and 223 pounds), and told the jury that they will see bodycam footage with conversations between the officers that the bystanders who filmed the event on their phones did not hear.

Mr. Nelson said the police officers made two calls for emergency medical care; the first was a call regarding Floyd’s injured nose, and the second was a “Code 3,” which heightened the urgency. When paramedics arrived, they did a “load and go” because of the angry crowd of bystanders at the scene. Floyd was quickly put in the ambulance, and paramedics began resuscitative efforts several blocks away. There were additional attempts to save Floyd at the hospital, but he was pronounced dead that evening.

Nelson said the only person who conducted an autopsy on Floyd was Dr. Andrew Baker, and he told the jury they will hear about interviews Dr. Baker had with law enforcement about his conclusion. Floyd had no telltale signs of asphyxiation, such as bruising to the neck, even beneath his skin, and no petechial hemorrhaging. There is no evidence that his airflow was restricted. Blood toxicology revealed the presence of Fentanyl and methamphetamine. Nelson described Floyd’s heart and lung issues, and revealed that Floyd had a paraganglioma tumor that secreted adrenalin.

On the actual cause of death, Nelson said, “Evidence will show that George Floyd died of a cardiac arrhythmia that occurred as a result of hypertension, coronary disease, the ingestion of methamphetamine and Fentanyl, and the adrenalin flowing through his body. All of which acted to further compromise an already compromised heart.” Therefore, he concluded that the only reasonable verdict would be to find Derek Chauvin not guilty.

The first witness on Tuesday was Donald Williams, one of the people who saw George Floyd die. He is a black man in his 30s, a former wrestler and professional MMA fighter who now works as a bouncer and security guard. His testimony began with a recording of his 911 call to the police to complain of what he thought was excessive force. In the call, Mr. Williams referred to Derek Chauvin as “Officer 987” because he had made the effort to remember his badge number. He got emotional as the recording played and let out a “Whew!” and wiped his eyes when it finished.

Mr. Williams composed himself when Mr. Chauvin’s defense lawyer, Eric Nelson, began cross-examination. Mr. Nelson recounted the previous day’s testimony, in which Mr. Williams discussed his training in choke holds. A “blood choke” is a wrestling hold that limits blood supply to one side of the neck and can render someone unconscious. At the scene of George Floyd’s arrest, Mr. Williams told Derek Chauvin that it looked as though he was using a blood choke. Mr. Nelson asked how long it takes for someone to pass out from a blood choke, and Mr. Williams said that it takes only a few seconds.

Mr. Williams refused to agree with Mr. Nelson that he had been angry, even after Mr. Nelson reminded him that he was on video cursing and calling Officer Chauvin names such as “tough guy.” Mr. Nelson reminded him that he had called Officer Chauvin “bum” 13 times and also called him “bitch.” “You can’t paint me to be angry,” Mr. Williams said, maintaining that his behavior had been “professional.” Mr. Williams had continued to argue with Officer Thao even after Floyd was put in an ambulance and removed.

As Mr. Williams recalled his feelings as he watched George Floyd pass out, Matthew Frank, a lawyer for the prosecution, asked him why he “got more and more angry.” Instead of denying that he was angry, as he had just done, Mr. Williams said it was because the police were not listening to him. Just before Mr. Williams was excused, Mr. Nelson asked if he was able to have a conversation with an opponent while the opponent was being rendered unconscious in MMA. Mr. Williams was taken aback by the question, and said “no.”

Minor witnesses were called next; none of their faces could be seen on TV. Prosecutor Jerry Blackwell, a black man, talked to a black girl named Darnella Frazier, who was 17 on the day of George Floyd’s arrest, and saw her life change after the 10-minute video she took went viral. She said, “It seemed like he knew it was over for him.”

Mr. Blackwell had her look at a photo of the bystanders, and asked if she would characterize the group as an “unruly crowd.” She said no; the bystanders were just reacting to what they were seeing. “It wasn’t right.” She testified that she did not see violence from bystanders, just from the cops. She said it was unfair to call the bystanders “a mob.”

Miss Frazier said she saw Officer Chauvin put his hand on his mace, and she felt threatened. “I felt like I was in danger when he did that.” As she filmed the arrest scene, Miss Frazier said it looked like Officer Chauvin was kneeling harder on George Floyd, “feeding on the energy” of the bystanders. Mr. Blackwell asked her if she saw Mr. Chauvin “let up or get up,” and she said no, but later mentioned seeing him get up when a paramedic motioned for him to do so.

Mr. Blackwell asked Miss Frazier how seeing the way George Floyd died had affected her life. She sighed. “When I look at George Floyd, I look at my Dad; I look at my brothers; I look at my cousins; my uncles, because they are all black . . .” Her voice began to quiver. “I have black friends, and I look at that, and I look at how that could have been one of them. There have been nights, I stayed up apologizing and apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more, and not physically interacting and not saving his life. But it’s not what I should have done; it’s what he should have done.”

Another witness was Alyssa Funari, a white 17-year-old girl who drove with a friend to “the corner store” and passed the scene of Floyd’s arrest. She parked nearby, and she saw that people standing on the sidewalk were in distress, and there was a man on the ground, also in distress. She borrowed her friend’s phone and got out of the car to film.

Miss Funari saw Officer Chauvin holding Floyd down with his knee, and could see other officers restraining him. Questioned by prosecutor Erin Eldridge, a white woman, Miss Funari described seeing George Floyd struggling to breathe. She said he was vocal at first, then became less so. “He was talking with smaller and smaller breaths, and he spit when he talked . . . If he were to be held down much longer he would not be able to live. . . His eyes were rolling back, and one point he just sat there.” Miss Funari started crying and Miss Eldridge paused her questioning to allow her to compose herself.

“It was difficult,” Miss Funari said, “Because I felt like there wasn’t anything I could do as a bystander. I felt like I was failing him.” She described feeling powerless because another police officer kept bystanders on the sidewalk, preventing them from getting close. She testified that the men restraining Floyd did not move much, but then observed that Officer Chauvin’s back foot came off the ground and he put his hand in his pocket. She said she saw Officer Chauvin’s knee move further down on Floyd. She said his knee remained on Floyd when the paramedics checked Floyd’s neck for a pulse.

The video Miss Funari recorded was shown in the courtroom; her voice is heard on the video, asking Officer Chauvin, “Why are you kneeing him more?!” After Floyd passed out, she walked away, but soon came back to film a second video. She explained that she walked away because it was hard to watch, but came back to the scene because she knew what was happening was wrong. Miss Funari was heard on her video, shouting to the officers, “It’s over a minute!” and she explained that she was worried “time was running out. He was going to die.” She added, “I kinda knew that he was dead or not breathing.” Miss Funari saw paramedics check Floyd’s eyes and take his pulse. She described feeling “emotionally numb,” afterwards, saying that she “didn’t rush to the internet,” and just tried to go on with her day. “It was a lot to take in.”

[Editor’s Note: The first half of this article covers testimony from Day 2. What follows after the “* * *” is testimony from Day 3.]

Kaylynn Gilbert, a white 17-year-old, told the jury that she was in court “for George Floyd.” She and her friend Alyssa had parked near Cup Foods, and Miss Gilbert stayed in the car while Alyssa got out to film, until the voices got louder and prompted her to get out, too.

Women rally in front of a large portrait of George Floyd in front of Cup Foods in Minneapolis (Credit Image: © Jack Kurtz / ZUMA Wire)

She saw Officer Chauvin putting pressure on Floyd’s neck that she felt was not needed, after Floyd appeared unconscious. She asked the police why they were still on top of Floyd. Miss Gilbert described Officer Thao’s tone of voice as “really hostile,” and said she saw him push one of the bystanders onto the sidewalk. She did not see any bystanders get physically aggressive, and said, “They were just using their voice.”

She thought Officer Chauvin’s body language looked “angry” as he was put his knee into Floyd’s neck, and she said that he grabbed his mace and shook it at her. She saw Officer Chauvin release Floyd after a paramedic signaled for him to do so.

“I didn’t know for sure if George Floyd was dead,” she said, “But I had a gut feeling.”

Genevieve Hansen, a white 27-year-old, came to court wearing her Minneapolis Fire Department dress uniform. Miss Hansen, a former lifeguard, went through Emergency Medical Technician training, earning state and national licenses, before beginning her firefighter training. She has been a Minneapolis Firefighter for two years.

On the day of George Floyd’s death, Miss Hansen was off duty and on a walk when she saw the lights of an emergency vehicle. Wondering if her coworkers were there, she went over, then saw a woman on the street screaming, “They’re killing him!”

Miss Hansen said she remembered seeing four officers putting their full weight on Floyd’s body, but “we know now” that there were only three officers restraining Floyd. “Three grown men putting a lot of their weight on someone is too much.” She described Officer Chauvin as “looking comfortable” as he held Floyd down with his knee, because he had a hand in his pocket and was not distributing his weight.

Miss Hansen said that Floyd’s face was “smushed to the ground,” and it “looked puffy and swollen.” She saw fluid on the ground and thought it was coming from George Floyd’s body. “In a lot of cases, we see a patient release their bladder when they die. I can’t tell you exactly where the fluid was coming from, but that’s where my mind went.”

Wanting to help Floyd, Miss Hansen said that she identified herself as a firefighter but did not show Minneapolis Fire Department identification; she had not brought it with her. Officer Thao told her, “If you really are a Minneapolis Firefighter, you would know better than to get involved.”

Miss Hansen disagreed with him. “That’s exactly what I should have done. There was no medical assistance on the scene . . . I could have given medical assistance.”

When asked what she would have done, Miss Hansen said that she would have called 911 for paramedics, checked Floyd’s airway, checked his pulse, and done chest compressions if there had been no pulse. Since Officer Thao wanted her to stay on the sidewalk, she shouted to the police, “If he has no pulse, you need to start compressions!”

Prosecutor Erin Eldridge asked Miss Hansen if she felt frustrated. She started crying and took a tissue, before saying, “Yes.”

In his opening statements, prosecutor Jerry Blackwell had told the jury that they would see examples of people “calling the police on the police.” Miss Hansen was an example of that. After the ambulance pulled away with Floyd inside, she called 911, asking to speak to a supervisor. She said that she did this because she was worried about black men who were still at the scene, but did not elaborate on why she was concerned about them. She ended her call when her coworkers from the nearest fire station arrived and went into Cup Foods, looking for a victim.

During cross examination, the defense showed that police had requested paramedics at 8:21, and Miss Hansen arrived at the scene at 8:26. Defense lawyer Eric Nelson asked Miss Hansen if she agreed that a paramedic had more training than an EMT, and she agreed. He asked if anyone had ever come up to her while she was fighting a fire to tell her she was doing it wrong, and she said, “No.” They discussed the fact that medical personnel do not go into a police scene until a Code 4 is called, indicating that it is safe.

There were times when Miss Hansen was defiant. Mr. Nelson asked if it would be reasonable to assume that if a patient were having a medical emergency and the police were present, that police had already called for Emergency Medical Services. Miss Hansen replied, “Your question is unclear because you don’t know my job. So, I can’t answer.” After a slight rephrase, she agreed that it was reasonable, but added a qualifier — she felt that the response time was not normal that day. When asked if she would agree that the other bystanders were angry, Miss Hansen said, in a mocking tone, “I don’t know if you’ve ever seen someone killed, but it’s upsetting.”

Mr. Nelson impeached Miss Hansen by providing documentation that she had told investigators last year that George Floyd was a “small, slim man.” Miss Hansen explained, “With three grown men on top of him, it appeared that he was small and frail.” Mr. Nelson responded with, “OK,” but she tried to keep speaking. “There was no question,” Mr. Nelson said. Miss Hansen said with an eye roll, “I was finishing my answer.”

Judge Cahill sent the jury out, then admonished Miss Hansen for interrupting:

Miss Hansen, I’m advising you. . . . You will not argue with the court. You will not argue with counsel. They have the right to ask questions. Your job is to answer them. I will determine when your answer is done. . . . Do not argue with the court. Do not argue with counsel. Do not volunteer information that is not requested. The attorneys for the state have redirect; they can ask you questions if they think that certain things were left out. It is counsel’s prerogative to ask you leading questions, and for you to answer those, and not volunteer additional information. Are we clear on this?

* * *

On Wednesday morning, witness #9 was called. Christopher Martin, a 19-year-old black man, lives above and worked at Cup Foods, the store where the incident took place. He testified that a man wearing red pants who was seated on the passenger side of Floyd’s car when Floyd was arrested had come into Cup Foods earlier in the day, and tried to pass a counterfeit bill, which Mr. Martin did not accept. The store had a policy that if an employee accepted a counterfeit bill, it would be deducted from his paycheck.

Later in the day, the man in red pants returned to the store with Floyd. Mr. Martin took notice of Floyd because of his large size. When Floyd came to the counter to make a purchase, Mr. Martin talked with him. Floyd spoke slowly, giving Mr. Martin the impression that he was under the influence. Floyd’s demeanor was friendly, but Mr. Martin suspected he was high.

Security footage from inside the store was shown for the first time, and Floyd could be seen moving in a way that was different from everyone else in the store. At one point, he seemed to be doing a strange dance. Mr. Martin said that Floyd used a $20 bill with blue pigment on it to pay for cigarettes. He suspected that the man in the red sweatpants knew he was using counterfeit money, but thought that Floyd might not realize the money was fake. Mr. Martin took the suspicious $20 and told his manager. Mr. Martin’s manager told him to go outside and ask Floyd to come back to the store. Mr. Martin did this twice, and both times, Floyd would not leave his car, so the manager called the police.

While Mr. Martin was still being questioned, Juror #7 raised her hand and left the courtroom, so the judge took a break. Court TV later reported that the juror left because she had an emotional reaction to the testimony, though it’s unclear which part upset her.

When court resumed, Mr. Martin talked about how Floyd reacted when he went to the car to ask him to come back to the store. He said that Floyd raised his hands and touched his head, in gestures that seemed to say, “Ugh, why is this happening?”

Mr. Martin was busy working when police came into the store, but when he heard the commotion outside and saw the store emptying, he followed the crowd to see what was going on. Like other bystanders, Mr. Martin took a video, but thinking that Floyd had died in front of him, he deleted his video.

After video taken from the outside of Cup Foods was shown to the court, showing Mr. Martin standing with his hands on his head. Matthew Frank — a prosecuting lawyer — asked Mr. Martin what he had been thinking. Mr. Martin said that he felt “disbelief and guilt” and that if he had accepted the counterfeit bill, this would not have happened.

The 10th witness was 61-year-old black man Charles McMillian. Mr. McMillian said he stopped his car when he saw police activity and got out to watch because he was “being nosey.” Mr. McMillian is the gentleman in the viral videos who encouraged Floyd to cooperate with police, telling Floyd that he couldn’t “win.”

The prosecution asked Mr. McMillian to review the video of himself witnessing the incident, and he broke down sobbing when Floyd started calling for his mother. He said that he had lost his own mother on June 25th, and he was so distraught that the lawyer asked for a break. The defense lawyer, Eric Nelson, did not cross examine Mr. McMillian.

The 11th witness was Lieutenant Jeff Rugel, a surveillance- and bodycam-video expert for the Minneapolis Police Department. During this portion of the trial, surveillance and bodycam footage from city-owned cameras on the street were entered into evidence, and jurors saw bodycam footage from the four arresting officers, including brief footage from Derek Chauvin’s own body camera, which fell off while he was struggling to get Floyd into the squad car.

Footage from all of the officers showed their struggle to get Floyd into the car. One officer, who was trying to get Floyd into the car from the door that opened toward the sidewalk, took care twice to keep Floyd’s head from bumping into the car as he tried to get Floyd to sit down. Floyd tried to get out of the car through the door facing the street, and kicked at Derek Chauvin and the other officer on that side. As Floyd tried to get out, he moved himself toward the ground, and an officer was heard saying, “Get him on the ground.” After Floyd was restrained on the ground, an officer is heard calling for an ambulance.

It was interesting to see footage of Officer James Alexander Kueng, a light-skinned black man, kneeling on Floyd right beside Chauvin, for the same length of time, not releasing Floyd until paramedics arrived. Later in the video, Mr. Chauvin looked concerned as he helped paramedics load Floyd into the ambulance.

Fencing erected around the Hennepin County Government Center in preparation for the trial of Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: Lorie Shaull via Wikipedia)

See our coverage of the first day of the trial here, the second day here, and the third day here.

The surprise of the day came when George Floyd’s girlfriend, Courteney Ross, told prosecutor Eric Nelson that she was saved in Floyd’s phone as “Mama,” Floyd’s pet name for her. This raised the possibility that the “Mama” Floyd called for as he was dying could have been his opioid-addicted girlfriend rather than his mother, who died in 2018.

Miss Ross, a 45-year-old white mother of two, got emotional when lawyer Matthew Frank began questioning her. Miss Ross first met Floyd in August 2017, when Floyd was working as a security guard at a Salvation Army shelter. Miss Ross had gone to the shelter to talk to her son’s father, who was staying there, about the child’s upcoming birthday. While she waited for him at the receptionist’s desk, Floyd approached her, saying, “Sis, you OK, Sis?”

Miss Ross did not feel OK and was especially touched when Floyd asked if he could pray with her. They shared their first kiss at that meeting. The couple continued to date, off and on, until Floyd’s death. She said that Floyd was a physically active man who lifted weights every day, did calisthenics at home, biked, and played several sports, especially football.

When asked about Floyd’s health, Miss Ross said that he complained about pain from injuries he had suffered to his neck and his back. She said he never complained about shortness of breath.

Their romance had a dangerous undercurrent. Both were opioid addicts, and Miss Ross described how the couple used drugs they were prescribed and ones from the black market. The pair took oxycontin and oxycodone pills throughout their three years together. In March 2020, Miss Ross took Floyd to the hospital because he was doubled-over with abdominal pains. This led to a five-day hospital stay; she later found out this was because Floyd had overdosed on heroin. When asked in cross-examination if Floyd had been foaming at the mouth when she took him to the hospital, Miss Ross said that there had been a dry, white substance on his mouth.

Miss Ross talked about the two people who were passengers in Floyd’s car when he was stopped by police on May 25, 2020: Maurice Hall and Shawanda Hill. Floyd often bought drugs from both of them. When she was interviewed by the FBI following Floyd’s death, Miss Ross speculated that Floyd obtained the heroin that led to his March 2020 overdose from Shawanda Hill, because he had gotten pills from her before.

March 2020 was a difficult month for Floyd. Miss Ross said that he had been clean and sober at the beginning of the year, but in March, his behavior had changed, and she was suspicious that he was taking drugs again. Then, they fell back into the habit of getting high together. That month, Floyd brought her some pills that looked thicker than the ones they normally took. Opioids usually made Miss Ross feel relaxed, but these thicker pills made her jittery, and kept her up all night.

A week before Floyd died, they got the unusual pills again. Miss Ross told the FBI that this time the thicker pills made her feel like she was “going to die.” She also told investigators that she noticed a behavioral change before his death: There were times when he would be bouncing around erratically and his speech would be unintelligible. The last time she had contact with Floyd before his death was over the phone a day before he died.

The two paramedics who were called to the scene of Floyd’s arrest also testified. Seth Bravinder and Derek Smith — both white men — said they were first dispatched to aid a civilian with a mouth injury. The urgency level was “Code 2,” meaning that the ambulance traveled with no lights or sirens. But en route, the call was upgraded to a “Code 3,” so the lights and sirens were turned on.

After arriving at the intersection of 38th and Chicago, near Cup Foods, both men reported seeing a man lying on the ground with three police officers on top of him. This made Mr. Bravinder think the man might struggle during treatment, but when he looked again, he did not see any breathing or movement. Mr. Smith noticed that Floyd’s chest was not rising and falling. When he checked Floyd’s pupils, they were dilated, and Floyd had no pulse. “In lay terms,” Mr. Smith said, “I thought he was dead.” He told Mr. Bravinder that he wanted to “move this out of here,” so they could begin care in the back of the ambulance. He motioned to Officer Chauvin to move off of Floyd. As Mr. Bravinder unloaded the stretcher, he also noticed a “crowd of upset, yelling people on the street,” and “wanted to get away from that,” and be in “a controlled space” so they could focus their energies on the patient.

A video of the scene shows Mr. Bravinder supporting Floyd’s head as he gets him into the stretcher. He explained that he wanted to keep Floyd’s head from slamming into the pavement, as Floyd was limp and unresponsive. Mr. Smith remarked that the police officers were “very helpful in moving the patient onto the canvas.”

Officer Lane went with them, and the three men tried to resuscitate Floyd, as the ambulance was driven three blocks away from Cup Foods. Officer Lane performed manual chest compressions (CPR). Mr. Smith unclothed and uncuffed Floyd to provide better care. He saw that Floyd had superficial injuries on his nose and shoulder, which would not cause cardiac arrest.

Mr. Bravinder saw a flatline on the heart monitor. With Officer Lane’s help, he placed a Lucas device on Floyd, which does chest compressions to circulate blood throughout the body. He also placed a device down Floyd’s throat to keep his airway free of fluid and help him breathe. A firefighter who had been called to help them also assisted. Mr. Smith administered epinephrine, an adrenaline shot used to jumpstart the heart. Soon after, the paramedics shocked Floyd with a defibrillator, but with no success.

Recently retired Minneapolis Police Sergeant David Pleoger was the last witness of the day. He was Derek Chauvin’s sergeant the day of Floyd’s death. If any of the sergeant’s officers use force, they do a “Force Review” report, which includes interviews with the officer and the victim. Officers have to notify the sergeant after use of force, but there are exceptions. When George Floyd was pronounced dead at the hospital, it became a “Critical Incident,” so Sgt. Pleoger was not involved in reviewing the use of force on Floyd as the review went “up the chain” and was taken over by other administrators.

On May 25, 2020, Sgt. Pleoger received a call from 911 dispatch operator Jena Scurry. Their recorded conversation was played in court. Miss Scurry said on the phone:

You can call me a snitch if you want to, but we have the cameras up . . . They must have already started moving him . . . I don’t know if they had to use force or not, but they got something out of the back of the squad, and all of them sat on this man, so I don’t know if they needed you or not, but they haven’t said anything to me yet.

“Yeah, they haven’t said anything. Must have been just a takedown, which doesn’t count, but I’ll find out,” Sgt. Pleoger responded. Sgt. Pleoger then called Officer Chauvin on his cell phone. Chauvin said: “Yeah, I was just gonna call you, have you come out to our scene here. . . We just had to hold a guy down. He was, uh, going crazy; he wouldn’t go in the back of the squad.”

Officer Chauvin told the sergeant that he and the other officers had tried to put Floyd in the car and that he became combative. Floyd injured his face while resisting, and after the officers struggled with him, Floyd suffered a medical emergency, so the officers called an ambulance. Officer Chauvin asked Sgt. Pleoger to head to the scene. Officer Chauvin did not say anything about putting a knee on Floyd’s neck or back, but the sergeant testified that a knee to the neck may not be a reportable use of force.

Sgt. Pleoger spoke with all four officers at once. They told him that their suspect had been handcuffed and taken away in an ambulance. He decided to go to Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC) to check on the suspect, and told Officers Lane and Kueng to stay by Floyd’s car. He told Officers Chauvin and Thao to go to HCMC too but to speak to witnesses first. Officer Chauvin said he could try to, but that they were hostile.

At HCMC, Sgt. Pleoger was taken to the stabilization room, where he saw a Lucas machine doing chest compressions on Floyd. He spoke with a nurse for a condition update, and she said that Floyd was doing poorly. He told a lieutenant about Floyd’s condition, and the lieutenant contacted Internal Affairs.

The lawyers asked Sgt. Pleoger about “positional asphyxia” and he said that MPD officers are trained on the dangers of it. If you leave someone on his chest or stomach too long, he can suffer breathing difficulty. A patient’s own body weight can cause positional asphyxia, even without another person pressing down on the patient. Sergeant Pleoger stated that he felt the police should have ended their restraint of Floyd after he stopped resisting.

Hennepin County Sheriffs Officers examine the scene where protestors have been since the beginning of the trial outside the Hennepin County Government Center during the Derek Chauvin Trial in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Credit Image: © imageSPACE via ZUMA Wire)

See our coverage of the first day of the trial here, the second day here, and the third day here, and the fourth day here.

On Friday morning, the prosecution called Lt. Richard Zimmerman, a white man who has been a Minneapolis police officer since 1981. He works in the homicide unit, and one of his duties is to respond to “critical incidents” in which someone dies. He reached the intersection of 38th and Chicago, at 9 pm, after Floyd had been taken the hospital. Police Sergeant Bob Dale arrived and told Lt. Zimmerman that Floyd had died, so this was a “critical incident.” Police put crime-scene tape around the intersection and locked down the area to preserve evidence. Agents from the State Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) took over, and took both the squad car and Floyd’s Mercedes Benz into custody.

Prosecutor Matthew Frank asked Lt. Zimmerman to explain the “Use of Force Continuum” to the jury. The lieutenant said that this is a Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) guideline for de-escalation, ranging from simply being present at the scene in uniform, to using deadly force. Force levels change according to the threat to the officer. Lt. Zimmerman said he was never trained to kneel on the neck of a handcuffed suspect in a prone position (lying face down). He testified that he received MPD training on the prone position and that the department considers it “deadly force.” When an officer has a suspect handcuffed and prone, he must get him on his side, so he can breathe easily.

According to Lt. Zimmerman, police are trained in some first-aid techniques, and get CPR training every other year. An officer must give first aid, even if he has called an ambulance.

Lt. Zimmerman reviewed the body camera footage of Officer Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd. He told the court that he believed this use of force was “totally unnecessary. . . . Pulling him down to the ground, face down, with a knee on the neck for that amount of time, it’s just uncalled for. . . . I saw no reason why the officers felt they were in danger, if that’s what they felt. And that’s what they would have to feel to use that kind of force.” Prosecutor Frank asked, “In your opinion, should that restraint have stopped once he [Floyd] was handcuffed and prone on the ground?” Lt. Zimmerman replied: “Absolutely.”

On cross-examination, defense attorney Eric Nelson pointed out that the lieutenant had not been a patrol officer for over 20 years, and that tactics and equipment have changed dramatically. He added that although the lieutenant had use-of-force training, he does not teach it to other officers. Mr. Nelson got Lt. Zimmerman to concede several points:

- Other factors may supersede an officer’s medical responsibilities. He must keep the scene secure and consider the safety of everyone in the immediate area, not just the person he’s arresting.

- There are times when an arrestee is unconscious but wakes up and becomes more combative than before.

- “Holding for Emergency Medical Services (EMS),” in which officers hold someone while they wait for EMS to arrive, is MPD policy.

- Sometimes police restrain a suspect for his own safety and the safety of others, not just for the safety of officers.

- An officer must consider whether he has the tactical advantage.

- Handcuffing can fail, and sometimes additional force is required. Perps have attacked officers using handcuffs as weapons.

- Use of force depends on “the totality of the circumstances.” It is a “dynamic series of decision-making . . . and it’s based on a lot of information that is not necessarily captured on a body cam.”

- In a fight for your life, you may use any force that is reasonable and necessary.

Mr. Frank began his redirect examination by having Lt. Zimmerman testify that he gets the most up-to-date training on use of force. Then he asked about the threat presented by the bystanders. Lt. Zimmerman did not think they were “an uncontrollable threat to the officers at the scene.” He said that the crowd “doesn’t matter. . . as long as they’re not attacking you.”

This was Mr. Frank’s final round of questions:

Mr. Frank: Does “Holding for EMS” excuse the officers from providing medical attention that they’ve been trained to provide?

Lt. Zimmerman: No, it doesn’t.

Mr. Frank: Does it excuse officers from continuing to use the decision-making model for use of force?

Lt. Zimmerman: No.

Mr. Frank: Did you see any need for Officer Chauvin to improvise by putting his knee on Mr. Floyd for nine minutes and 29 seconds?

Lt. Zimmerman: No, I did not.

Judge Cahill adjourned for the day.

Day Six started with an intriguing but mysterious ruling by the judge that there had been no juror misconduct. He did not say what the misconduct might have been.

Before the jury came in, the prosecution objected to the admission of the entirety of some officer bodycam video. Judge Peter Cahill asked if a particular piece of video was a way to get Floyd’s state of mind in “through the back door.” Earlier, he had ruled that Floyd’s state of mind is not relevant. The judge allowed one video of Officers Lane and Kueng, but not another.

There was also some discussion about admissibility of further prosecution evidence about use of force. Judge Cahill allowed it, but said it must be brief, saying “We’re not going to ask every officer, ‘What would you do different?’ ”

After the jury was seated, it heard from Dr. Bradford Langenfeld, the ER doctor who pronounced Floyd dead. He told the court that he was the primary medical decision-maker for Floyd, and that when Floyd was brought in, his heart was not beating. The primary goal was to get the heart beating again, and to try to find out why it had stopped beating, in case the reason was reversible.

Dr. Bradford had received a message from Emergency Medical Services (EMS) that they would be bringing in a 30-year-old male in cardiac arrest, so the doctor prepared a bay with critical care equipment and prepped a team for Floyd’s arrival. The doctor told prosecutor Jerry Blackwell that, at the time, he had not seen any video of what had happened to Floyd.

When Floyd arrived at the ER, there was a Lucas machine attached to him, rhythmically compressing his chest to keep blood circulating. The paramedics gave the doctor a report that said they were called to treat someone detained by the police who had facial trauma, and the call was upgraded to an emergency. The patient had no pulse when he arrived. They gave Floyd an airway tube, medication, and CPR. They followed protocol for treating patients with cardiac arrest, and tried to revive Floyd for 30 minutes. The paramedics did not say that Floyd suffered a drug overdose or had had a heart attack. The doctor explained that there is a 10-15 percent decrease in chance for survival for every minute that CPR is not administered after the heart stops beating.

The Lucas 2 chest compression system. The external mechanical device provides chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. (Credit Image: © Larry Fisher / Quad-City Times / ZUMAPRESS.com)

When Floyd arrived at the hospital, his heart had some pulseless electrical activity, which suggested bleeding or low oxygen. The monitor later showed a flat line. Shocking the heart with a defibrillator would not have done any good for a patient in Floyd’s condition. The doctor used ultrasound to rule out possible causes for the cardiac arrest; there had been no internal bleeding. There was no report from EMS that Floyd had overdosed on a specific drug, so the doctor did not consider drug antidotes. The paramedics had not reported typical symptoms of a heart attack, but the doctor said that heart attack could not be ruled out. Dr. Langenfeld ultimately decided that “one of the more likely” reasons Floyd’s heart stopped beating was hypoxia — he did not have enough oxygen.

At the end of 30 minutes, the doctor pronounced Floyd dead. (In Minnesota, only a physician can declare a patient dead.) Floyd’s heart had been stopped for 60 minutes and there was no possibility of resuscitation. The prosecutor asked if death from lack of oxygen is also called “asphyxia,” and Dr. Langenfeld said yes.

Under cross-examination, defense lawyer Eric Nelson asked if drug use could cause hypoxia, and the doctor said it could. Mr. Nelson inquired about Floyd’s high carbon dioxide levels, and whether that could be caused by Fentanyl. Dr. Langenfeld said that it could; the “primary reason” Fentanyl is so dangerous is that is depresses the lungs. A high carbon dioxide level causes shortness of breath, even without stress. The doctor also said that Fentanyl causes sleepiness, and Mr. Nelson said in his Opening Statement that he would produce a witness to testify that Floyd was very sleepy before the police showed up.

The next witness was Minneapolis Chief of Police, Medaria Arradondo. Much court time was devoted to reviewing the Chief’s qualifications, his tenure with the MPD since 1989, and all of the steps as he rose through from patrol officer to Chief of Police. The chief explained how the MPD is structured. The Police Officer Standards of Training (POST) board grants the license to become a sworn police officer, and officers need continuing training to keep their licenses.

April 5, 2021: Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo testifies about department training, procedures and ethics on the sixth day of the trial of former Minneapolis Police Officer Chauvin. (Credit Image: © Pool Video Via Court Tv via ZUMA Wire)

On the day George Floyd died, the deputy police chief told Chief Arradondo that someone taken into custody was not expected to survive. After Floyd was pronounced dead, the chief was able to see what happened from footage from a city-owned camera, but all he could see were the backs of officers, and there was no audio. That video showed nothing disturbing. He was not able to see Floyd at all until the paramedics put him on a gurney. Close to midnight, a community member contacted him and said, “Chief, have you seen the video of an officer choking and killing that man?” After that, the chief saw the bystander video.

He reviewed the bystander video and the body cam footage of all of the officers. Based on that, the chief does not think Officer Chauvin followed the MPD’s de-escalation policy, and that restraint should have stopped “once Mr. Floyd had stopped resisting, and certainly once he was in distress and trying to verbalize that.”

All Minneapolis police officers get a policy manual, and are required to know the policies. The jury viewed many pages from this manual, and heard the chief’s opinion that Officer Chauvin violated policy. Both Mr. Chauvin and his defense lawyer were vigorously taking notes during the discussion on de-escalation policy, which the chief defined as “stabilizing situations with the goal of a safe and peaceful outcome.” He said that use of force can be part of de-escalation, or the opposite of de-escalation, depending on the circumstances. The chief also said that de-escalation can include “seeking the community’s help.”

Chief Arradondo talked about the concept of “meeting our community where they are.” He said, “It may be the first and last time they have an interaction with a Minneapolis police officer, and we have to make it count.” Police officers are expected to be able to deal with a wide variety of behavior from people they meet during 911 calls, and sometimes they will encounter someone who will not comply with commands. Police officers have to make their own assessment about whether the person they are dealing with is in crisis, and can be considered an EDP (Emotionally Disturbed Person). “People in crisis may not have brought it upon themselves,” the chief said, adding that those who did bring the crisis on themselves must still be treated according to MPD policy.

Chief Arradondo also said, “We recognize that we are often going to be the first to respond to someone who needs medical attention and so we absolutely have a duty to render that aid.” An officer must request EMS and use his first-aid training. The chief said that Officer Chauvin violated policy when he failed to give aid when Floyd lost consciousness.

Police officers carry Narcan kits. This is an inhaler that helps save someone who has overdosed. Only the Fire Department used to carry Narcan, but since the increase in opioid overdoses, the police have been trained to use Narcan.

On use of force, Chief Arradondo said, “The one singular incident we will be judged forever on will be our use of force. So while it is absolutely imperative that our officers go home at the end of their shift, we want to make sure our community members go home too, and so sanctity of life is absolutely vital.”

He said neck restraints and choke holds are taught and authorized by MPD policy, and he classified the neck restraint he saw Officer Chauvin using in video footage as a “conscious” neck restraint, one that was not intended to render someone unconscious. An unconscious neck restraint is authorized only if an officer is in fear of bodily harm.

In cross examination, Eric Nelson asked an intriguing question: Was Chief Arradondo familiar with “Camera Perspective Bias.” The chief said he was not. Camera Perspective Bias refers to the fact that the point of view from which you see an event can change your opinion of it.

Two videos were shown in court, both separately and side-by-side. The side-by-side version matched the timing of the two videos, so you could see the same event from two points of view. One video was taken by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier with her phone and the other was video from Officer J. Alexander Kueng’s body camera. From Darnella Frazier’s perspective, it looks like Officer Chauvin had his knee on George Floyd’s neck — but Police Chief Arradondo agreed that from the perspective of Officer Kueng’s body cam, Officer Chauvin’s knee was on Floyd’s shoulder blade. Up until that moment, the chief said he thought the knee had been on Floyd’s neck.

The last witness of the day was Inspector Katie Blackwell of the police department, who was commander of a training division on the day Floyd died. She said she had known Officer Chauvin for 20 years, and that at one time they had worked the same shift. She said that as a training commander, she had chosen Officer Chauvin to be a Field Training Officer (FTO) to train police recruits.

Documents were entered into evidence to show that in 2016, Officer Chauvin had 40 hours of FTO training for this purpose, and that he took a shorter, “refresher” course in 2018. Miss Blackwell testified that FTO medical training includes CPR, opioids, positional asphyxia, etc. She said that officers are told that a prone handcuffed position can cause asphyxia, so they need to get someone in that position on his side as soon as possible.

She was shown a photo that is a screenshot from bystander video that seems to show Officer Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd’s neck. “This is not what we train,” Miss Blackwell said, adding that she had no idea what technique Officer Chauvin was improvising. The day ended after brief cross-examination by Mr. Nelson.

April 6, 2021: Former New York Gov. David Paterson joins representatives of the Floyd family at the Hennepin County Government Center in Minneapolis where testimony continues in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. (Credit Image: © TNS via ZUMA Wire)

Court began with a hearing without the jury present. The lawyer for Morries Hall, the man who was in the passenger seat when police came to arrest George Floyd, wanted to quash (invalidate) the defense subpoena for him to appear in court. George Floyd’s girlfriend had testified that they bought illegal drugs from Morries Hall. Mr. Hall now wants to invoke his 5th-amendment right not to incriminate himself by testifying. His lawyer told the court that any activity on May 25th, both before and after police arrived, could incriminate Mr. Hall:

There is an allegation that Mr. Floyd ingested a controlled substance as police were removing him from the car; a car that has been searched twice, and from my understanding, drugs have been found in that car twice. This leaves Mr. Hall potentially incriminating himself into a future prosecution for third degree murder.

The charge would be: “Whoever, without intent to cause death, proximately causes the death of a human being by, directly or indirectly, unlawfully selling, giving away, bartering, delivering, exchanging, distributing, or administering a controlled substance.”

Derek Chauvin’s defense lawyer, Eric Nelson, agreed to submit proposed questions for Morries Hall and his lawyer to review. A decision on his testimony is expected in the coming days.

After the jury was called, Sgt. Ker Yang, a Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) Crisis Intervention Training Coordinator, took the stand. He defined “crisis” as “any event or situation that is beyond the person’s coping mechanism or beyond their control.” The goal is to bring a person in crisis back to pre-crisis level. Examples of crisis include mental health emergencies, reactions to a car crash, drugs, intoxication, etc. According to MPD policy, officers should try to de-escalate a person in crisis, when it’s “safe and feasible.”

Sgt. Yang remembers that Officer Chauvin attended one of his training sessions. The MPD hires professional actors for crisis intervention training. They act out roles in which police officers deal with simulated real-life crises. Training also includes a decision-making model with five basic steps:

- Information Gathering — Can be based on a dispatch or officer’s observation. “Listening is key.”

- Threat/Risk Assessment — Assess risk based on information.

- Authority to Act — Based on policy and city statutes for use of force, crisis intervention, and de-escalation.

- Goal and Actions — See if the person needs help and what kind of help.

- Review and Reassess — See if your technique is working, and if not, adjust it as more information becomes available.

Sgt. Yang believes this is a useful model, and that it can be used in a quickly changing situation. The sergeant said he thinks his training works.

On cross-examination, Sgt. Yang said that the critical decision-making model itself is not policy. Mr. Nelson asked if crisis intervention means the officer has to consider that it could become a crisis for bystanders, and the sergeant said that is correct, acknowledging that when police use force, it can “look bad” to the public, even if the officer’s actions are lawful. Therefore, the behavior of onlookers is part of decision-making. Officers are trained to look for signs of aggression in a suspect and observers, such as: standing tall, muscle tensing, getting red in the face, and raised voices. Mr. Nelson emphasized that an officer has to consider the “totality of the circumstances” when making decisions, a point he has brought up with previous witnesses.

Sergeant Yang said that a “crisis” could include an overwhelming event, such as seeing something upsetting, or taking drugs. The sergeant agreed that an officer may have to deal with several people in crisis at once and has to consider everything when he takes his next steps. Officer Chauvin was dealing with many people in crisis on the day George Floyd died. As the level of crisis intensifies, the risk to the officer rises. An officer is trained to stay calm, not let anyone get too close, appear confident, and avoid staring at people. What an officer hears, such as people making threats, goes into his decision making.

The defense emphasized that according to MPD policy, in a crisis, all decisions are about what is “safe and feasible.” The prosecution emphasized that an officer always needs to keep in mind his legal “authority to act.”

Next on the stand was Lt. Johnny Mercil, a MPD use-of-force instructor who knows martial arts, particularly Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. Jiu Jitsu often uses body weight instead of striking to apply force. Documents shown in court prove that Officer Chauvin took training from Lt. Mercil in 2018.

The lieutenant’s testimony began with a definition of use of force:

Any intentional police contact involving:

- Any weapon, substance, vehicle, equipment, tool, device or animal that inflicts pain or injury to another.

- Physical strikes to the body.

- Physical contact to the body that inflicts pain or injury.

- Restraint applied in a manner or circumstance likely to produce injury.

Lt. Mercil added that use of force must be reasonable when it starts and when it stops. As levels of resistance decrease, the officer should decrease use of force. Police officers are taught to use the least amount of force for any purpose, such as putting people in handcuffs. Policy states that “a peace officer making an arrest may not subject the person arrested to any more restraint than is necessary for the arrest and detention.”

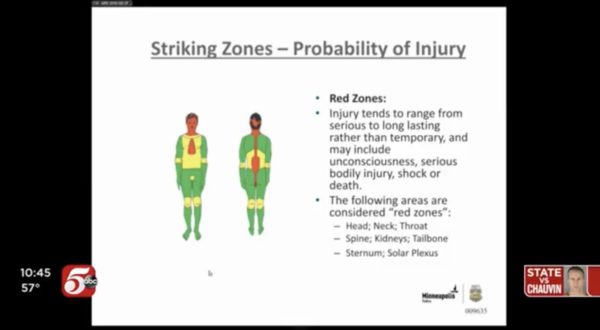

The jury was shown an image of the human body used to train officers on where they should or shouldn’t hit a suspect. The head, neck, spine, and tailbone were in the “red zone,” meaning that “injury to those areas tends to range from serious to long lasting, and may include unconsciousness, serious bodily injury, shock or death.”

This expert witness confirmed that MPD policy allows neck restraints. In general, a neck restraint is considered non-deadly force. It puts pressure on the side of the neck to slow blood flow to and from the brain. Light to moderate pressure is a controlling technique, and maximum pressure can make a person blackout.

Lt. Mercil said that he taught police officers to put the subject’s neck in the crook of the arm, and apply pressure with the forearm and upper arm. He never taught anyone to use a knee in a neck restraint. He did train people to use a leg, but to apply pressure with the thigh. Police officers may use conscious neck restraint against subjects who are actively resisting. The unconscious neck restraint may be used only:

- On subjects who are actively aggressive.

- For life-saving purposes.

- In order to gain control of an actively resisting subject and if lesser attempts at control have been or would probably be ineffective.

A neck restrain is not authorized on someone who is not resisting. When Lt. Mercil was asked to give his opinion of the photo of Officer Chauvin with his knee on Floyd’s neck, he said it is not the kind of neck restraint MPD trains officers to do, but that it is authorized. When asked how long this technique should last, Lt. Mercil said that it would depend on the type of resistance from the subject. He said it would not be authorized if the subject were handcuffed and under control. Lt. Mercil said that a “choke hold” is considered “deadly force,” but that in the video he saw, he did not see Officer Chauvin use a “choke hold” on Floyd.

Lt. Mercil explained that handcuffs go on one cuff at a time, and when the officer has control, he needs to check the fit and the double-lock. The double lock prevents further tightening — for the comfort and safety of the arrestee — and keeps the cuffs closed. Lt. Mercil said that when someone is handcuffed face-down, he teaches officers to use a knee to control the subject’s shoulder. “You put one knee on each side of the arm, so one would be on the upper shoulder and one would be one the back. And then isolate the arm, present the arm for cuffing.” He added that when the subject stops resisting, that is not necessarily the time to remove the knee, because people can still thrash around and be a threat. “They can kick, bite, and some other things. So control doesn’t end with handcuffing.”

He also said that once the subject is compliant, that’s a good time to remove the knee. After that, an officer should get the subject in another position, such as the “side recovery” position, which allows better breathing, or let him stand or sit. Prosecutor Matthew Frank asked, “How soon should you place the person in side recovery?” Lt. Mercil said, “When the scene is Code 4 and you’re able to do it. . . . The sooner the better.” (Code 4 means that the scene is safe.)

The lieutenant also testified about “maximal restraint technique,” or the “hobble,” in which an officer ties the legs of the subject so he can’t kick. The officer should then puts the subject on his side. “When you restrict their ability to move, you restrict their ability to breathe.”

Lt. Mercil agreed with the defense that people make excuses when they are arrested. In the past, he had had to decide if a suspect was making excuses or was really having a crisis. He arrested people who claimed to be having an emergency and said, “I can’t breathe” to avoid arrest. Sometimes Lt. Mercil thought they were lying.

Mr. Nelson showed the lieutenant a photo of a paramedic checking George Floyd’s carotid pulse by feeling the side of Floyd’s neck while Officer Chauvin still had his knee on him. “In your experience, would you be able to touch the carotid artery if the knee was on the carotid artery?” Lt. Mercil replied, “No, sir.”

The defense then showed a screenshot from one of the officers’ body cameras, that showed Officer Chauvin holding Floyd down. Lt. Mercil agreed that Officer Chauvin’s shin appeared to be across Floyd’s shoulder blade, not on his neck. There were two other screenshots with different time stamps that also showed Officer Chauvin’s shin across Floyd’s shoulder blade.

When he looked at a fourth photo that showed Officer Chauvin’s knee, the lieutenant said this seemed to be a “hold,” not a neck restraint. He conceded that it’s possible he had to hold someone down for 10 minutes in his own police career, and that he had held people down while waiting for Emergency Medical Services. He has trained officers to do this.

The court viewed photos from a training manual that show an officer putting a knee on a subject’s shoulder, with his shin across the neck. This is a technique for handcuffing someone in a prone position. An officer may need to stay in that position for a while, but Lt. Mercil said that officers must be mindful of the neck. He also testified that he had been taught that if someone can talk, he can also breathe.

The next expert witness, Nicole MacKenzie, a MPD medical support coordinator who trains officers in first aid, said that she does not teach that if someone can talk he can breathe. She said it’s possible that a talking person may not be breathing adequately. Officer Chauvin attended one of her courses, which included CPR training, a Narcan (antidote for certain drug overdoses) update, and casualty care.

Miss MacKenzie said the department’s policy is that you need to give CPR and call an ambulance when someone is in critical condition. She went over steps for treating an unresponsive person. If he has no pulse, officers are trained to do CPR. They may stop if the situation is not safe or if they are exhausted and cannot continue.

Miss MacKenzie talked about “agonal breathing,” which is gasps that do not give someone enough oxygen. She called it “the brain’s last-ditch effort to get air.” She told Mr. Nelson that agonal breaths can be misinterpreted as effective breathing, and it’s easier to make that mistake if there is a lot of noise and commotion.

She was asked if she was familiar with “load and go,” which means putting a patient in the ambulance and leaving as quickly as possible to treat him elsewhere. This is what paramedics did with George Floyd. Miss MacKenzie agreed that the people in the area affect an EMT’s decision to load and go. Miss MacKenzie said this happens if you have a very hostile crowd. “Bystanders sometimes do attack.” She said hostility is “a growing contingent of people . . . yelling, being even verbally abusive to those that are trying to provide scene security.”