When ownership is the only hobby left – Washington Examiner

The passage discusses the concept of “hobbies” in a modern context, using a recent YouTube video by Hodinkee featuring actor Daniel Dae Kim discussing his passion for purchasing wristwatches. Unlike traditional hobbies that involve creativity or skill, such as woodworking or painting, the “hobby” promoted by Hodinkee focuses solely on the acquisition and ownership of high-end watches, a practice referred to as “curation.” This term,which traditionally applied to museums,has broadened to encompass various forms of collection across different interests,including sneakers and vinyl records.

The distinction between curation and collection is highlighted, with curation being more about financial capability and social validation through ownership, as opposed to the more involved process of collecting that entails research, restoration, and historical significance. The text critiques the trend toward superficial acquisition,exemplified by social media influencers who engage in unboxing items without any interactive enjoyment of the products. Many young American men are drawn to curation and video games, which the author suggests are both ultimately unfulfilling pursuits. The narrative raises questions about the nature of hobbies and the meaningful engagement with our interests, contrasting the joys of traditional hobbies with the more transactional nature of modern curation.

When ownership is the only hobby left

Two weeks ago, the YouTube channel Hodinkee released a video featuring noted Lost actor Daniel Dae Kim, in which he spent 37 uninterrupted minutes talking about … buying watches in retail stores.

Not acting, his personal life, or his experience as a Korean-born artist building a career in the United States. Just the purchase and ownership of mass-production wristwatches from various billion-dollar brands. Going into the store, seeing the watches, handing over the credit card — that sort of thing. The video was well-received, with one commenter noting that he “LOVED this conversation. This is what our hobby is all about! Thanks for posting, Hodinkee!”

Which leads to an obvious question for many readers, namely: What, exactly, is “our hobby”?

The most common 19th- and 20th-century idea of “hobby” was as an activity with some room for creative effort, demonstrated physical mastery, or a combination of both. Woodworking, painting, acoustic guitar, Civil War reenactment — that sort of thing. One takes joy first in doing it at all, later in the accomplishment, or perhaps the hope, of doing it well. It’s possible to be bad at a hobby, which is not to say that one does not enjoy it still. Often the goal is to create something unique, or at least individualized. As an example, very few people set out to crochet something identical to what can be bought in the store down the street.

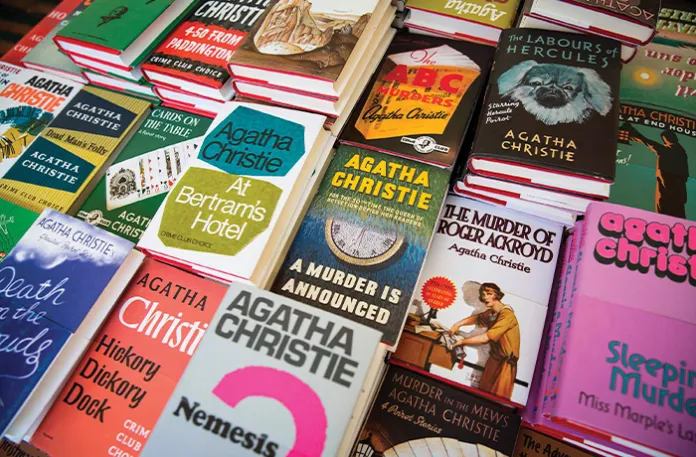

The “hobby” promoted by the Hodinkee YouTube channel and website is something quite different from any of the above. Hodinkee, which raised $40 million in funding and was valued at $100 million for years before its $14.4 million sale to the Watches of Switzerland retail chain late last year, is entirely devoted to the purchase and ownership of upscale wristwatches. It’s not a watch-repair hobby site — that would be TimeZone — and it’s not for the people who build their own watches and/or extensively modify them — that’s WatchForum.com. Rather, Hodinkee is just for people whose lives revolve around the purchase and ownership of brand-new, standard-issue watches from Rolex, Omega, Seiko, and other major brands. The people who engage in and obsess over this behavior don’t call it “the purchase and ownership,” of course. They call it “curation.”

If you think we hear that word a lot more than we used to, you’re right, because it used to follow just two words, “museum” or “gallery,” but is now uncritically applied in newspapers of record to describe people who have strong opinions on basketball shoes from 1983-1989. People “curate” their vinyl records, their Funko Pops dolls … and their wristwatches, too.

Curation is considerably simpler than most traditional hobbies. There might be 20 different skills involved in building a wooden cutting board, but curators need and, indeed, can only have but two: the ability to buy and the ability to choose. The former is measured in dollars and it determines the scope of your curation. The latter is usually measured in the approval of others within the “hobby,” and it determines your curation’s makeup. You don’t need to actually use the things you buy — in many cases, this detracts from their resale value. Ownership is the ostensible point, and that exciting frisson of purchase is the hit that keeps the marks coming back for more.

The most notorious curators, especially in the male-centric interests of watches, firearms, and sports cars, are “finance people,” who are often highly compensated but can’t make time for traditional, effort-intense hobbies. Curation can be done via the web while you attend a meeting or wait for an email. You need not leave your job to participate. When you do eventually get home, a simple picture of what you’ve bought will get you the requisite kudos on social media, at which point you can put the item in question away and get back to work.

While not quite a religion, curation does have priests of a sort in the “hobby influencers” whose entire social media persona revolves around receiving free things from sponsors and gushing about said items on camera. It also has a sacrament: the “unboxing video” in which a brand-new product is unwrapped and removed from its packaging while an unseen narrator offers a running commentary on the quality of the presentation. Sometimes, the object in question is used afterward, but just as often, it is discarded or set aside. After all, the point of the experience is to purchase and then unbox. Anything more would be both unprofitable to the sponsors and beside the point to most of the curators.

Is curation the same as collection? Not according to auto-racing legend and alpha car collector Miles Collier, whose landmark, both in the sense of its significance and the actual physical size of the book, The Archaeological Automobile, begins by sharply delineating between the historically significant practice of collection and the mere ego exercise of accumulation. Researching, finding, and restoring an example of every major road-racing Ferrari model to compete during the ’60s? That’s collection. It has a guiding principle, some obvious rules, and a foreseeable end. Buying every brand-new Ferrari and Lamborghini that arrives at your local dealer? That’s “accumulation.” Collier, whose uncle won the Watkins Glen SCCA race in 1949 before dying while leading the 1950 event, is merciless in his contempt for the accumulators, the mere purchasers, the curators.

Yet curation of one form or another appears to be in a dead heat with video games for the title of “most commonly encountered obsession among young American men.” Both of these nonhobbies are fundamentally soul-sucking — the video game substitutes the imaginary and meaningless for the real world of challenge and accomplishment beyond the screen while curation offers nothing but a never-ending treadmill of purchase, unboxing, storage, and eventual disposal. In neither of these is anything created, accomplished, or even truly enjoyed. There is nothing but mere consumption, whether it is the purchase of “downloadable content” in Call of Duty or the anticipated arrival of a Rolex Submariner at the local jeweler. There’s something particularly sad about the latter — imagine spending $12,000 or more on a watch designed to survive depths in the ocean beyond which a mere glimmer of light can reach, unboxing it on TikTok to a chorus of likes and comments, then very carefully putting it back into its box so you don’t scratch it, ever.

It’s easy for people such as your 53-year-old author to be smug and dismissive about curation as a meek little lifestyle for the meek little boys of those generations following mine. I am writing this a few dozen feet away from the sports-prototype-car Radical SR8 in which I regularly risk limb, if not life, racing at 150 miles per hour a few inches away from other, equally unhinged competitors. Yet for me to do so is ignorant and unsympathetic. The Gen Z “product manager” or junior broker who “curates” his watch collection doesn’t have the time, the space, or the mechanical ability to race a car. He likely lives in an apartment roughly the size of my motorcycle storage loft and spends a dozen or more miserable hours per day between work, commuting, meals, and other unavoidable time thieves. He may have grown up without much access to a father or other male role model. He may not know how to use tools or even how to identify them.

For young men such as these, the idea of making one’s own furniture or even building a frigate in a bottle is almost beyond comprehension. Who’d inspire them, or help them, or join them in the effort? It is far easier to just scan the internet, pick something to curate, join the Reddit community on the subject, and then spend the rest of one’s youth … curating. “Just got the call” from my authorized watch dealer, he’ll post. “Finally the owner of a Rolex Submariner.” Then it’s back to the email, the meetings, the jobs that can’t be explained to an 8-year-old and which have never appeared in any edition of Richard Scarry’s Busy, Busy World, the proverbial life of quiet desperation unleavened by the creative joy of building a table or even playing a bad cover of “Wonderwall” on the acoustic guitar.

Which is not to say that all is lost. The same internet that tirelessly drives the consumption of unworn watches and undriven sports cars also harbors communities of people who build things from scratch, create new forms of music and art, and “mod” everything from computer keyboards to single-engine airplanes. These challenging and often dispiriting passions and pursuits are not as easily undertaken as mere curation, nor do they offer the sort of immediate gratification for which we’ve conditioned at least two generations of young men. But they offer something unavailable in any store: the joy of accomplishment. Spread the word to curators of all sorts, from lonely apartment-dwellers to famous actors: There is more joy in heaven and earth than is dreamt of in your purchase-centric philosophy.

Jack Baruth was born in Brooklyn, New York, and lives in Ohio. He is a pro-am race car driver and a former columnist for Road and Track and Hagerty magazines who writes the Avoidable Contact Forever newsletter.

" Conservative News Daily does not always share or support the views and opinions expressed here; they are just those of the writer."